15 Fun Facts About Ice Cream History You Probably Didn’t Know

Ice cream’s past is far stranger and more inventive than most people realize. Long before it became a freezer staple, it moved through royal courts, early laboratories, wartime ships, and bustling fairs, picking up new techniques and traditions along the way. What this really means is that every scoop carries pieces of global history, from ancient chilled dairy drinks to the first industrial factories and modern science that perfected texture. Looking at these milestones shows how a simple frozen treat kept evolving with culture, technology, and taste.

1. Ice Cream’s Early Roots In Ancient China

The story of ice cream starts long before freezers, in the royal courts of ancient China. During the Tang dynasty, records describe a chilled mixture made from fermented buffalo, cow, or goat milk combined with flour and camphor, cooled with ice harvested from winter stores. This was not ice cream as we know it, but it shows that people were already experimenting with sweetened, frozen dairy as a luxury for the elite. Similar ideas appear later in Persia and the Middle East with sherbet-like ices. What matters for history is that the basic concept of freezing sweet liquids or dairy for a special treat was circulating in Asia centuries before it hit European kitchens or American soda fountains.

2. The First Industrial Ice Cream In The U.S. Started In 1851

Modern ice cream really takes off when someone figures out how to make it in bulk. In the United States, that turning point came in 1851, when Baltimore milk dealer Jacob Fussell began producing ice cream on an industrial scale. Using surplus cream that might otherwise go to waste, he set up a dedicated factory to churn and freeze large quantities, then ship them to cities by rail. That move cut costs and made the dessert available to more than just the wealthy. Commercial ice cream parlors and vendors began spreading through urban areas as railroads, ice distribution, and later mechanical refrigeration improved. Fussell’s operation is often cited as the first large-scale American ice cream factory, and it marks the shift from homemade luxury to an emerging mass market product.

3. Chocolate Ice Cream Came Before Vanilla

Most people assume vanilla is the original, but chocolate actually appears earlier in written ice cream recipes. In the 18th century, European cooks already used cocoa and drinking chocolate in custards, iced drinks, and frozen desserts. The flavor was associated with fashionable chocolate houses and elite dining. Vanilla, on the other hand, was harder to source and much more expensive, since it depended on orchid cultivation and manual pollination techniques that were not widely available until the 19th century. Early ice cream books from Italy and France include chocolate-flavored ices and gelati before vanilla appears as a common option. So while vanilla would later become the standard base flavor in North America, chocolate holds the historical edge as one of the first widely recorded ice cream flavors.

4. A Single Gallon Of Ice Cream Uses A Lot Of Milk

Behind a simple scoop sits a serious amount of dairy. On average, producing one gallon of traditional ice cream requires several liters of milk, depending on the fat content and recipe. Industrial formulas often start with a mix of whole milk, cream, and sometimes milk powder to hit a target butterfat range, usually between 10 and 16 percent for standard ice cream. The rest of the volume includes water from the milk, sugars, stabilizers, and air whipped in during freezing. The fact that so much milk is needed helps explain why ice cream was historically tied to regions with strong dairy industries and why price and availability fluctuated with milk supply. Even in the era of plant-based alternatives, classic dairy ice cream still represents a significant use of milk in many countries.

5. New Zealand Leads The World In Ice Cream Eating

When people think of big ice cream consumers, they often picture the United States, but New Zealand regularly ranks at or near the top for per-person intake. Estimates vary by year, yet numbers often show New Zealanders eating more ice cream per capita than almost any other country. Several factors support this habit. The country has a strong dairy sector, a culture of outdoor leisure, and a preference for simple, scoop shop-style treats. Classic flavors like hokey pokey, a vanilla base with honeycomb toffee pieces, have become part of the national identity. High per capita consumption also reflects how widespread ice cream is in everyday life there, from seaside shops to supermarket tubs, rather than being reserved for holidays or special occasions.

6. The Ice Cream Cone Took Off At The 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair

The idea of putting ice cream on or in baked wafers existed in Europe earlier, but the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair is where the cone really exploded in popularity. Multiple vendors later claimed credit, yet the shared theme is simple. Fairgoers needed a portable way to eat ice cream while walking the grounds. Nearby waffle or wafer sellers reportedly rolled their products into cone shapes and used them as edible containers. Visitors loved the combination of cold ice cream and crisp cone, and newspapers helped spread the image of the cone as a modern treat. Within a few years, specialized cone-baking machines appeared, and ice cream cones became standard in parlors and street carts. What had been a novelty at a fair turned into a defining part of how many people still experience ice cream today.

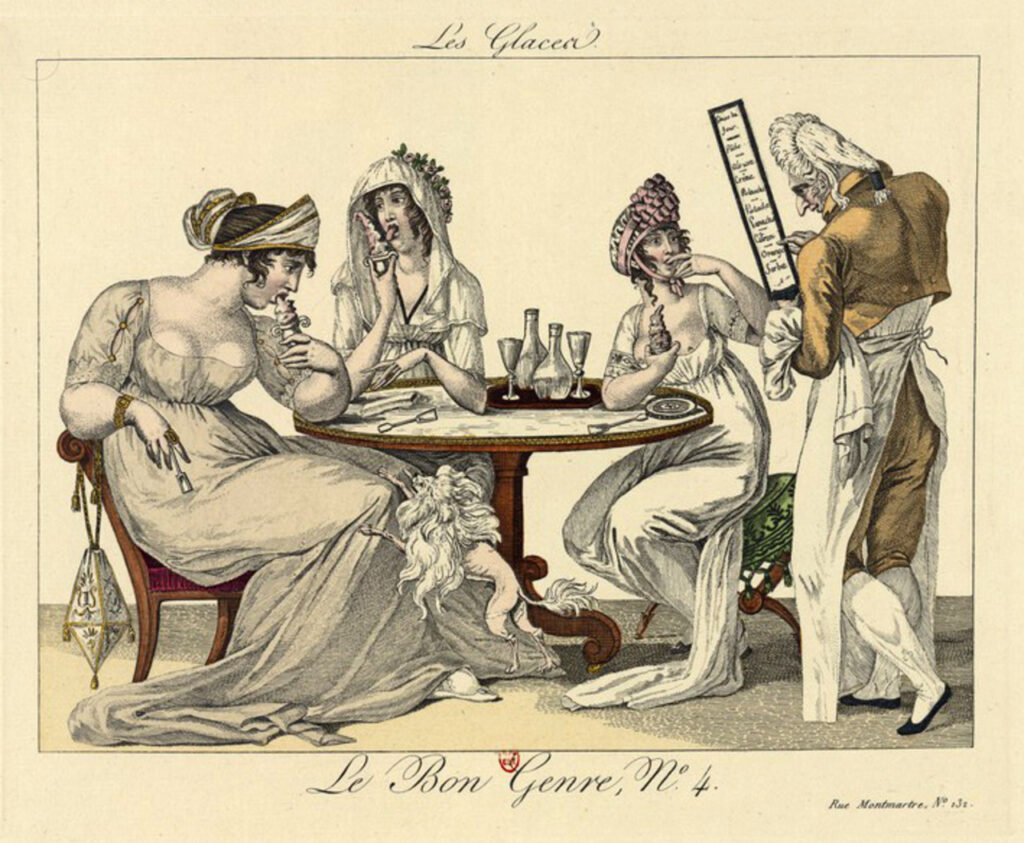

7. Custard-style ice Cream Took Shape In Early Modern Europe

The ice cream most people recognize today, with milk, cream, sugar, and egg yolks churned into a smooth custard, developed in Europe as freezing technology improved. In the 17th and 18th centuries, European cooks gained access to salt and ice mixtures that could bring containers below the freezing point of water, allowing more controlled freezing than simple snow storage. French and Italian recipe books from this period describe iced creams and flavored custards that were frozen while being stirred, which helped break up large ice crystals. These desserts were served in aristocratic households and at royal courts before gradually reaching coffee houses and public establishments.

8. Before Refrigeration, Ice Cream Was A Seasonal Luxury

Long before electric freezers, ice cream was limited by access to natural ice. In colder climates, workers cut blocks of ice from lakes and rivers during winter, then stored them in insulated ice houses packed with straw or sawdust. This ice could last into summer and was used to cool drinks and freeze desserts for wealthy households and urban businesses. Preparing ice cream required time, labor, and a reliable ice supply, so it remained a luxury associated with special occasions and upper-class dining. In warmer regions, only importers or those with high resources could maintain ice stores.

9. The Hand-Cranked Freezer Smoothed Out Ice Cream

A key shift in ice cream quality came with the invention of the hand-cranked freezer in the 1840s. Instead of relying on slow, manual stirring of a pot set in ice, this device used a crank to rotate a metal canister surrounded by a salt and ice mix. As the handle turned, paddles inside continuously scraped the freezing mixture from the sides, breaking up ice crystals and folding in air. This process produced a smoother, more uniform texture and reduced the effort needed to freeze a batch. It also made small-scale production more practical for households and small shops. The same basic principle still underlies modern batch freezers, though motors have replaced human cranks.

10. Ice Cream Became A Wartime Morale Booster In World War II

By the mid-20th century, ice cream had become such a familiar comfort food in the United States that the military used it to lift troop morale during World War II. The U.S. Navy famously deployed a floating ice cream barge in the Pacific to supply ships with frozen treats, and various improvised methods were used to freeze ice cream mixtures using the cold at high altitudes or in shipboard refrigeration systems. Serving ice cream on holidays or after difficult operations helped provide a small sense of normalcy and pleasure for service members stationed far from home.

11. Ice Cream Floats Turned Soda And Cream Into A Classic Pair

Ice cream floats show how easily a simple idea can become a nostalgic staple. In the late 19th century, soda fountains were popular social spaces where carbonated drinks flavored with syrups were served. At some point, operators began dropping a scoop of ice cream into a glass of soda or root beer, creating a mix of creamy foam and sweet fizz. Different regions and brands put their own twist on the combination, but the basic structure remained the same. Floats were appealing because they combined two existing treats without any special equipment beyond a fountain and a freezer.

12. Ice Cream Sundaes And Blue Laws Intertwined

The origin of the ice cream sundae is tangled in local rivalries, but one common thread involves Sunday restrictions on alcohol sales in parts of the United States. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, so-called blue laws limited what shops could sell on Sundays. Soda fountains that once mixed boozy concoctions turned to elaborate ice cream dishes instead. By serving ice cream topped with flavored syrups, fruit, nuts, and whipped cream, they created a special treat that felt indulgent without breaking the rules. Some accounts say the name “sundae” grew out of serving these creations on Sundays, later respelled to avoid religious sensitivities.

13. Oyster Ice Cream Proves Flavors Once Went In Strange Directions

Modern ice cream flavors can get playful, but unusual combinations are not new. Historical cookbooks from the 18th and 19th centuries include savory ice creams like Parmesan and even versions flavored with oysters. These recipes treated ice cream as a broader category of frozen dishes rather than strictly sweet desserts. Oyster ice cream, for example, was closer to a chilled, enriched oyster soup frozen into a mold, potentially served as part of a multi-course meal. The fact that such recipes existed highlights how differently earlier diners thought about temperature and flavor. Over time, sweet dairy-based flavors dominated the category, and savory ice creams became curiosities rather than mainstream offerings.

14. Ice Cream’s Texture Depends On Air, Fat, and Tiny Ice Crystals

What makes ice cream feel creamy instead of icy comes down to structure. Ice cream is a frozen foam, built from ice crystals, tiny air bubbles, fat droplets, and a continuous phase of sugary water and milk proteins. During churning, air is incorporated into the mix and fat droplets partially destabilize, forming a network that traps the bubbles and stiffens as it freezes. Stabilizers and emulsifiers, such as egg yolks or plant-based gums, help keep the mixture smooth by slowing ice crystal growth. If crystals become too large, the ice cream feels coarse on the tongue. The balance of fat and sugar also influences how hard or soft the product is at freezer temperatures.

15. Refrigeration Turned Ice Cream Into A Global Staple

The biggest change in ice cream’s story is not a single recipe or flavor, but the spread of reliable refrigeration. Mechanical ice-making and later electric freezers removed the dependence on natural ice and allowed manufacturers to produce and store ice cream year-round. Cold chains for transport and supermarket freezers for retail made it possible to sell tubs and novelties far from any dairy farm or ice house. This shift transformed ice cream from a seasonal luxury into a widely available product across income levels and climates. It also encouraged the growth of large brands, franchised scoop shops, and international styles, from American-style pints to Italian gelato displays.